Are you attracted to the idea of allowing people to decide for themselves what they work on, encouraging them to move towards the work they find most motivational, but something is holding you back from trying it? Perhaps you’ve heard of organisations that have run team self-selection events and, while that’s sounded to you like the right thing to do, you’ve thought “that’ll never work here”? Well, that is how Redgate’s product development organisation felt at the end of 2018.

This is the story of how we took the plunge, ran our own style of team self selection process and what happened as a result.

Spoiler: Good things happened.

Some context: What we believe at Redgate

At Redgate we believe the best way to make software products is by engaging small teams empowered with clear purpose, freedom to act and a drive to learn. We believe this because we’ve seen it; teams who have had laser-like focus on an aim, decision-making authority and the space to get better at what they do, were the most engaged and effective.

If you have read Dan Pink’s seminal book Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us, you might recognise that our beliefs echo what the author demonstrates are key to an engaged and motivated workforce — autonomy, mastery and purpose. Pink debunks the myth that the best way to motivate people is through monetary reward alone. Instead he proves, through the scientific studies he references, that you should compensate people fairly “to take the issue of money off the table” and then pay attention to three factors that will increase employee’s satisfaction and performance; people’s desire to be self-directed, their urge to get better skills and their need for what they do to have meaning and contribute to something bigger.

To keep true to our beliefs, Redgate needs to ensure that the goals and expectation of our teams are crystal clear, that we push authority to teams as much as we can and we encourage people to grow. We also recognise that different people have different ambitions, preferences for work and views on what counts as personal development. At Redgate, we have a large portfolio of products, written in a variety of languages, structured in a variety of ways and that exist at various stages of the product life cycle. That’s a lot of variety, and people are going to favour some combinations over others. They may also see a change of combinations, moving to work on something they have never worked on before, as an opportunity for personal growth.

As we believe that paying attention to people’s drive to learn is important, we knew we should allow people to take on work that they are drawn towards, either because they feel it will suit them better, they want to gather new experience or they like things just as they are. In the past we’ve always allowed people to move teams — everyone could proactively talk to their line manager at any point to kick-off a process that would result in a team move. But that wasn’t enough. We needed to do more than just allowpeople to move. Team bonds are strong and it is difficult to break the inertia of working in a team you are comfortable in. Instead, we needed to make it really easy for people to move, by creating a opportunity for a change, making it a truly reasonable thing to do and being clear on the options available. We had to articulate the differences in the work available across the organisation and then shake things up; encouraging, coaching, pushing people to move towards work that will motivate them.

Our worries about self-selection

Of course, we were a little anxious about what might happen if we gave people agency over which team they were in. What if nobody wanted to work on Team X because everyone wants to do work on Y? What if team Z was left with people who did not have the skills to really succeed with Z? The risks to efficacy of the development organisation seemed pretty significant. However, even more concerning for me was an instinct that the process may exert a great pressure on individuals as people would be asked to decide which team they would like to work in for the foreseeable future and to make the decision in a compressed period of time, maybe even during a single meeting. My instincts told me that could cause a great deal of anxiety for the people involved.

So, we took inspiration from (rather than copied from) the likes of Heidi Helfand’s popular conference keynotes about “dynamic reteaming” and Dan North’s tales of “delivery mapping” and decided to take an approach that mitigated our concerns but, we hope, kept true to the ideals of self-determination.

What we wanted to change in December 2018

At the end of 2018 Redgate explored and strategised over what it wanted to achieve in the following year. It became clear that as a result of those plans a number of our development team’s missions were going to significantly change. Furthermore, to do what we wanted to do we needed to expand from 10 development teams to 11 and create a new group of teams exploring early stage ideas searching for product market fit. And on top of that, while we had the hood up on the organisational engine, we wanted to be more deliberate about calling out where in the product life cycle our teams were operating. We grouped the teams working on our products and solutions based on something akin to Kent Beck’s 3x model. In our case our three areas of active development would be named:

- Explore – Ideas searching for product market fit.

- Exploit – Products and solutions looking to widen their serviceable addressable market.

- Sustain – Successful products that have reached maturity and now need to maximise return on investment.

We hoped the clarity of these phases would help teams shape their goals, processes and techniques to better suit the commercial environment they were operating in.

To summarize the changes we were making; we wanted to change what some teams worked on, create one new team, explicitly explore some new product areas and group teams by life cycle stage. A complex change to undertake, but one that would correspondingly create many new personal development opportunities for our people to take on. Finally, we wanted to give everyone a strong influence on where in the new team structure they would work.

Our approach to team self-selection

As I explained above, we wanted to keep to the principles of self-determination but to try to make the process as open, fair and low-pressure for everyone.

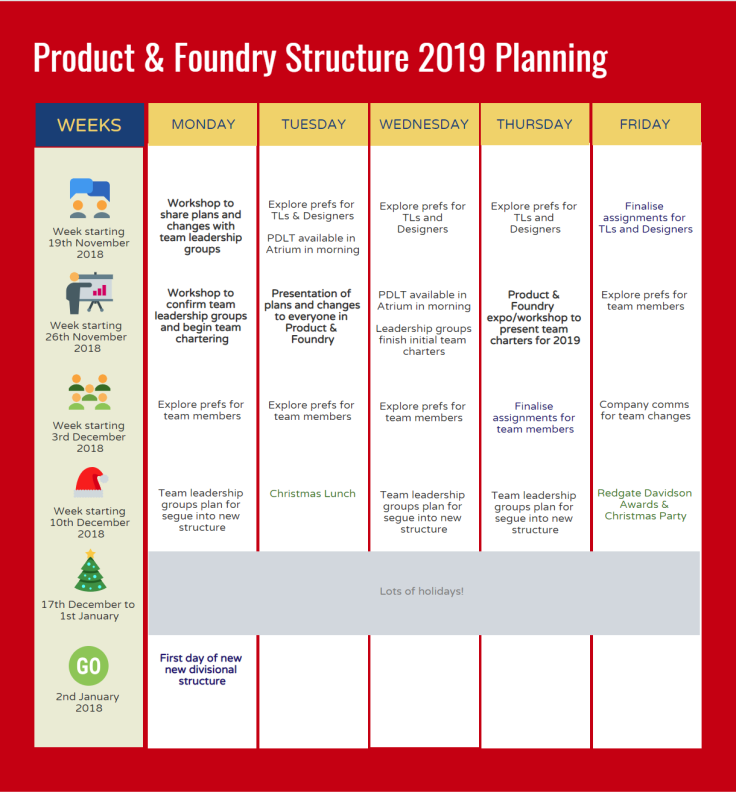

At a high-level, we wanted our approach to heavily involve our team leadership roles in shaping and rolling out the changes, to be transparent, to provide as much support as possible for the people involved and, ultimately, to allow everyone to take on work that motivated them. I’ll go into the detail of the process we used in a follow-up post but, in the meantime, here are the steps we took:

- We explained the big picture to team leadership roles (tech, product and design), including the reasoning behind the changes.

- We engaged leaders in shaping the plans, getting their advice on how to improve our ideas and the next steps.

- We got the leaders for each team in place in the new structure first, giving them the opportunity call out if they wanted to try something new.

- We shared our plans, reasoning and expectations with everyone in product development at a all-hands meeting.

- We asked leaders to provide more details on what life would be like in their teams in 2019. The populated a simple team charter to help present this information.

- We ran an open session for everyone to explore what life will be like on our teams in 2019 and to consider whether they would prefer to stay with their current team or move to another team.

- We coached everyone one-on-one to help them explore their options and help them decide. This was a big investment, but worth it.

- We asked people to tell us their 1st & 2nd preferences for their team for 2019 and the reasoning behind those preferences, but we made no promises as to whether we’d be able to meet them.

- We took a step back to see how people’s preferences lined-up with the big picture we needed to create. This did work, but it was tricky.

- We validated the new structure with team leaders and worked with people that did not get their preferred team.

- We made the team moves actually happen, ensuring teams were set up to start well.

After this process, the solution to the great team puzzle was agreed and everyone knew where they were going to be working at the start of 2019.

What was the result?

By the end of the process over 33% of people in the development organisation had moved teams, with every team having team members leave or new team members join. We had teams working on three new product areas, reduced investment in a couple of other areas and refreshed the mission for every single group. We achieved this change in 20 working days – from initial sharing of the plan to people literally sat in their new teams.

Most people were able to work in their 1st preference team, almost everyone was able to have their 1st or 2nd preference and only 2 people out of a department of ~75 people did not get either preference. We took special care to talk in detail to those two people, relying on their “Why” to explore options that might work for them. While not exactly happy with the outcome, I am thankful that those folks agreed to give the teams we suggested a try (and I can say now, over 9 months down the line, that those teams have proved to be a great fit).

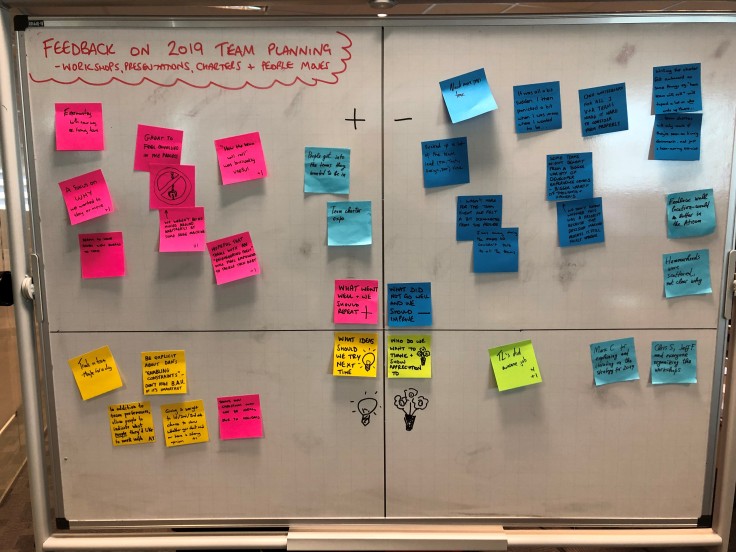

Although the resultant team structure and the smoothness of the process seemed like a great outcome to the product development leadership team, we were keen to know how people involved in the moves experienced things. So, we wheeled a big whiteboard into the centre of the office and asked people to give us feedback on the approach. Here’s what they shared…

Here’s some highlights from the feedback, assuming you can’t make out the writing on the post-its:

What went well and we should repeat

- Great to feel involved in the process

- “How the team will roll” was brilliantly useful

- A focus on WHY we wanted to stay or move

- “Engineering focus” teams should feel empowered to tackle tech debt

What did not go well and we should improve

- It was all a bit sudden. I then panicked a bit when I was unsure where I wanted to be…

- Missed expo so a bit disconnected from the process

- Doing over Christmas may not be ideal due to holidays

- Team charters will only work if they’re seen as living documents

What ideas should we try next time

- Giving a weight to 1st/2nd/3rd preference

- In addition to team preferences, allow people to indicate what people they’d like to work with

- Trials in teams – maybe for a day?

Nine months later…

I am writing this in September 2019, nine months on from the team changes, and I can now reflect on whether our approach was genuinely successful. Were the teams we created healthy? Did they deliver for the business and our users? Did people like working in their new team?

Well, our new or significantly changed teams all hit the ground running on 2nd January 2019; they gelled quickly, new missions were enacted and valuable software delivered to our users without missing a beat. Our teams’ OKRs have progressed well, the quality of our products has not dropped off a cliff and out customer satisfaction ratings are still tracking proudly in the high nineties.

Not only that, our always-on employee satisfaction survey shows us that during the period people’s satisfaction with their team and their sense of purpose increased. People’s already high satisfaction with their line manager was maintained, even though many of them moved to a new manager as part of the process.

In the months since, have we had difficulties in teams? Yes, of course we have, product performance is not always what you’d like it to be, gnarly code can delay process and humans working together will always have a few crossed-words from time to time. But I can honestly say that the level of these day-to-day challenges is no higher to what is was before we tried self-selection. I have no data for this, but my instincts tell me many of these things happen a bit less often now. But then I would think that, I guess.

Overall, I’m proud we achieved all this with a team self-selection process; putting the preferences and motivations of our engineers, designers and development leaders at the heart of the change.

Epilogue: Hang on, is that really team self-selection?

It’s possible people committed to faster self-selection processes feel the above is a bit of a cop-out; a team allocation process curated by managers, rather than true self-organisation. I can understand that perspective. But I think our way was better.

The reason I was reticent to undertake a reorganise yourselves into new teams in an afternoon approach is not because I was worried I was going to lose control of the process. Nor did I avoid it because I was concerned that self-organisation would not produce teams that were “fit for purpose” – as there are ways to facilitate self-selection meetings to ensure constraints are respected. I am committed to the idea that people need purpose, mastery and autonomy to really unlock job satisfaction, leading to high performance. That means giving people autonomy to move towards work that is motivational for them, as the purpose aligns with something they believe in, and work that will allow then to develop further mastery.

No, the reason I find short self-selection events unpalatable is the anxiety that a pressurised event may exert on it’s participants and the disadvantage more introverted or unconfident people would find when having to negotiate a position on a preferred team. How can there not be significant stress caused by a meeting that, effectively, gives each participant a goal of getting themselves onto the best team for them, their careers and their personal relationships in a 2 hour window, knowing they will have to live with their choice for many months. I can think of a number of my more confident, assertive colleagues that would secure themselves a fine role during an event like that. I can think of many more people who would find the whole exercise fraught with worry and would end up with leftover roles.

Instead of a short event, I feel that the more measured, drawn-out approach to re-forming teams we used garnered the benefits of self-selection without the drawbacks. We kept true to the principle of allowing people to take on work they found more motivational, while reducing the anxiety of change for people, putting introverts and extroverts on a level playing field. By giving everyone a one-on-one coaching session to explore what they were thinking, we ensured people genuinely considered their options in a supportive environment.

In the end, all this allowed us to create a solution to the great team structure puzzle that gave everyone a role for 2019 that they could feel motivated by.

Leave a comment