In my previous post, I explained why Redgate wanted to give people a strong influence over what they worked on, our concerns about team self-selection events and how we decided to approach the idea at the end of 2018. I also covered what feedback we received in the immediate aftermath of the changes and reflected on the results nine months later.

This post explains in much more detail exactly how Redgate ran it’s first formal team self-selection process, in the hope someone outside the company might find it useful.

Our aim was to keep to the principles of self-determination but to try to make it as fair and low-pressure for everyone. As a function of the process we were looking to make the following changes to the shape and remit of our eleven product development teams:

- Change the responsibilities of a number of our teams,

- Create one brand new team and disband another,

- Explore some new product areas,

- Group teams by life cycle stage and reset expectations as a result.

This was a complex change to undertake, but one that was important for Redgate’s plans for 2019 and one that would correspondingly create many new personal development opportunities for our people to take on.

So, here’s exactly how we did it:

1. We explained the big picture to team leadership roles, including the reasoning behind the changes.

At the very start of the process, we (the development organisation’s leadership team) gathered people responsible for leading our teams (our Technical Leads, Product Designers and Product Managers) together to share our ideas. We wanted their help to shape and improve our plans and then join us in rolling out the changes more widely.

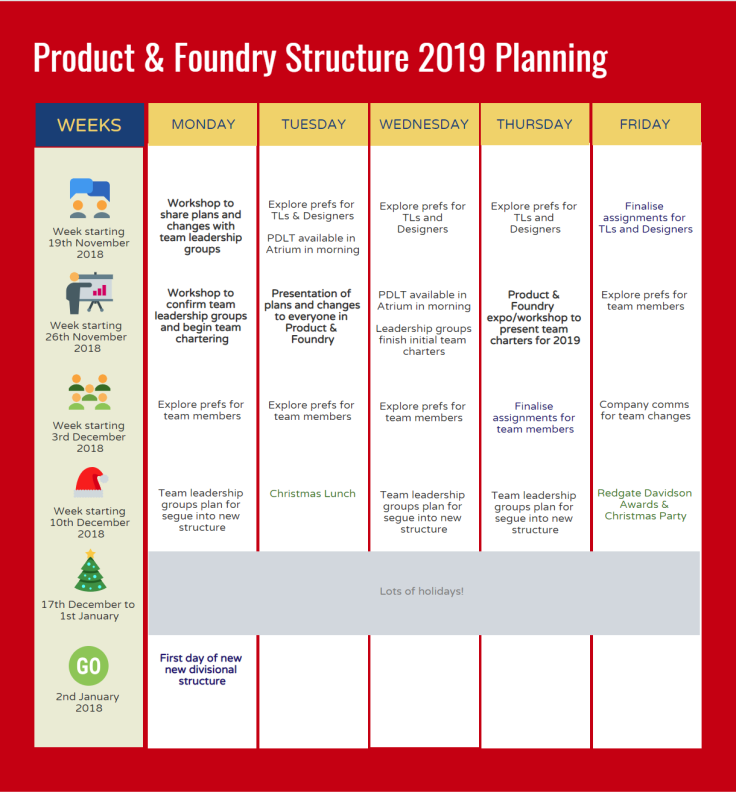

We presented the changing needs of the business in 2019 and outlined our ideas for grouping teams by life cycle stage. We were careful to explain the reasons behind these changes — the all important Why — and made a commitment to get their feedback on what we’d presented. We also shared the high-level plan for the process (see below).

2. We engaged leaders in shaping the plans, getting their advice on how to improve our ideas and the next steps.

Following the presentation we ran a workshop (centred around Liberating Structures’s Fishbowlactivity, facilitation fans) with the team leaders to answer their many questions and gather their feedback on what they had heard. That feedback was absolutely vital in helping us improve our plans, removing some elements of the team groupings that did not make sense, clarifying points around key concerns and reframing some of the messaging behind decisions.

What was clear at this point was that the leaders had just as much anxiety about where they might work in the new setup as anyone else. So we needed to get that decided first.

3. We got the leaders for each team in place in the new structure first.

Having explored and helped improve our plans, we gave leaders a few days to mull over where they wanted to work themselves. In that time they had depth chats with their line managers and considered their options.

To be honest, given the importance we place on our lead roles, it would have been difficult for us to support a high number of them moving from their established teams and still ensure the organisation maintain knowledge in key areas. But giving them the option to ask for a move if they want to was the right thing to do and, as it turned out, most of them wanted to continue to work with the team they currently lead.

4. We shared our plans, reasoning and expectations with everyone.

We were then in a great position to clearly explain the changes and the process to everyone in product development. We had an all hands meeting where we stepped through the plans for 2019 and how we wanted people to have a strong influence over what they worked on in the new year.

The most important thing we did in the session was to be very clear about the timetable for the changes and what people could expect from the process. We provided an array of avenues for people to ask their (many) questions about the changes — they could talk to their now up-to-speed team leads, contact us on Slack/Email or attend a number of drop-in sessions with the development organisation’s leadership team. Our people made use of all of these, raising fair questions and concerns — most of which we were able to answer well because of the initial feedback phase we took with the team leaders.

5. We asked leaders to provide more details on what life would be like in their teams in 2019.

Broadly, the plan from here was for people to explore their options at an open session two days after the all hands meeting, where team leaders would be on hand to explain their mission, plans and the shape of the team they would need for 2019. This meant we needed the team leaders to really engage in the task of providing a vision and plan for their team and it’s work in the next year.

As a thinking and presentation tool, we drew up a Team Charter template (below). This encouraged leaders to think about the why the teams will exist, what they will own, what impact they are going to aim for, how they will do their work, and so on. Our team leaders spent time discussing and honing their charters ready to chat them through with prospective new team mates at the upcoming workshop.

6. We ran an open session for people to explore their options in depth.

Our team leaders then set-up in our largest collaborative space (our canteen, the brilliantly named “SQL Servery”) to run an open information sharing session, armed with their Team Charters and the narrative behind its content. We invited everyone in development to drop in and out of the session, challenging them to “explore what life will be like on your team and the other teams in 2019” and “consider whether you would prefer to stay with your team or you have a preference for a move to another team”.

The session was a great success thanks to our brilliant team leaders and the engagement and professionalism of the entire development organisation. People explored the charters carefully and formed a clearer picture of what might be motivational for them.

7. We provided coaching and support for people 1-on-1 to help them explore options and decide.

Gathering all that information at the open session was invaluable, but the key step was to derive insight and preferences from it. We needed to help people answer questions about what kind of work they wanted to do? Whether they were best placed learning about this tech or that? Which team will give them the opportunities they need to progress their career aspirations. It is these deeply personal questions that can be missed or go unanswered during a “shut everyone in a room and only let them out when the new teams are decided” team self-selection approach.

Instead, we took a collective step back following the team charters workshop and made sure every single person in our development teams had a one-on-one session with their manager or leadership person to explore their thoughts and aims. That was a big time investment for our leaders, but it was worth every second.

8. We asked for team preferences and reasoning, but made no promises.

To draw that exploration to a close, we asked everyone to communicate their thoughts about where they’d like to work. We requested the following information:

- Their first preference for their team for 2019. This could be a preference to stay with their current team.

- Their second preference for their team for 2019. This could not be the same as their first preference.

- The reasons behind those preferences — “The Why”.

Throughout this process we were keen to emphasise to everyone that, although we would do our best, we could not make guarantees to meet people’s preferences. We needed to balance what was best for individuals, our teams and Redgate. It would be brilliant if we could give everyone their first preference, but it was improbable that everything would land that way.

An explanation of the “Why” behind people’s preferences was perhaps the most important thing we asked for from our people. We heard that people wanted to move for a variety of reasons, such as getting to grips with web technologies, working on a product earlier in its lifecycle or doing something new after many years working in the same area. Those key insights helped us see where we could create options, ensuring people had their needs met but in ways they had not envisaged.

9. We took a step back to see if we were close to what we needed.

At this point, my team of development managers and I then had so see how people’s preferences lined up with the big picture. So, we set up camp in a meeting room, drew the final shape of the organisation up on a whiteboard wall, represented people’s preferences with post-it notes, and started to piece together the puzzle. We had a single Elephant in the Roomquestion to answer — was this actually going to work?

And guess what? It did work! But it was tricky.

To make what I think is a key aspect of this success clear, our development teams are purposefully constrained to be a consistent size and shape — one technical lead, five developers and a designer. We could flex that a little, but only by +/- one developer. Furthermore, part of each team’s chartering process was to call out the balance of skills and experience they ideally needed in the team, such as “at least two people with prior web dev experience” or “three people who have worked on SQL Monitor before”. I think it was these constraints around the final picture that meant we understood what the solved puzzle should look like and allowed us to make best use of people’s first and second preferences to shape our answer.

Unsurprisingly, once we had assembled a picture using everyone’s first preferences, we had a few significantly over-populated teams and a few under-populated. We were then able to use second preferences, coupled with each person’s Why behind their preferences, to almost entirely complete the puzzle!

There were, of course, a couple of people for whom we could not juggle things in order to accommodate their preferences. However, we were able to examine the reasoning behind their preferences to identify another team option that might be a good fit for them. As with the best puzzles, creating those options necessitated knock-on changes — such as the odd person having to fall back to their second preference.

I have no doubt this step was key to the success of the process, but I do recognise this stage looks most like the “managers go into a locked room and decide all the things” approach we were keen to avoid. I can only assure the reader that we did this objectively, carefully considering the bigger picture but with our duty of service to the people in the organisation always in mind.

10. We validated the new structure with team leaders and worked with people that did not get their preferred team.

Once we had a solution to the puzzle we went back to the leaders of the teams to give them a chance to influence and commit to the shape of the team they were inheriting from the process. I’m pleased to say that the proposed teams met with universal approval. I think this was primarily down to conversations had at the open charter session and everyone’s confidence that each team was populated with people who were clearly motivated to take on their upcoming work.

We went back to talk, one on one, with everyone that had not got their first preference. This was a relatively small group of people. We took special care to talk in detail to people for whom we had not been able to meet either of their preferences, instead relying on their “Why”. While not exactly happy with the outcome, I am thankful that those folks agreed to give the teams we suggested a try (and I can say now, over 9 months down the line, that those teams have proved to be a great fit). It’s worth calling out that it was just two people in that situation — moving to a team they had not identified as a preference — out of a development organisation of ~75 people.

After all these discussions, the solution to the great team puzzle was agreed and everyone knew where they were going to be working at the start of 2019.

11. We made the team moves happen, ensuring teams were set up to start well.

The final step was to make those team moves happen. All at pretty much the same time, ready for a new start on the first week back at work after our Christmas break. And then to ensure that all those new and changed teams were able to hit the ground running, nurturing a healthy team culture and embarking on their new missions.

The answer to this was simple. Set the target that we wanted the new teams to be in place on January 2nd 2019, empower the team leaders to organise who in their new teams can move when (and to treat the target date pragmatically, if they needed to) and provide a set of common team building and direction setting tools that the teams could all make use of to set themselves up for success.

On 2nd January 2019

By the end of our team self-selection process over 33% of people in the development organisation had moved teams, with every team having team members leave or new team members join. We had teams working on three new product areas, reduced investment in a couple of other areas and refreshed the mission for every single group. We achieved this change in 20 working days (excluding the days between Christmas and New Year, when most people were out the office), from initial sharing of the plan to people literally sat in their new teams.

If you want to find out more about how people in the teams found the process or whether the resultant teams were healthy, check out my previous post.

Leave a comment